MLitt Art Writing School of Fine Art

Madeleine Kaye

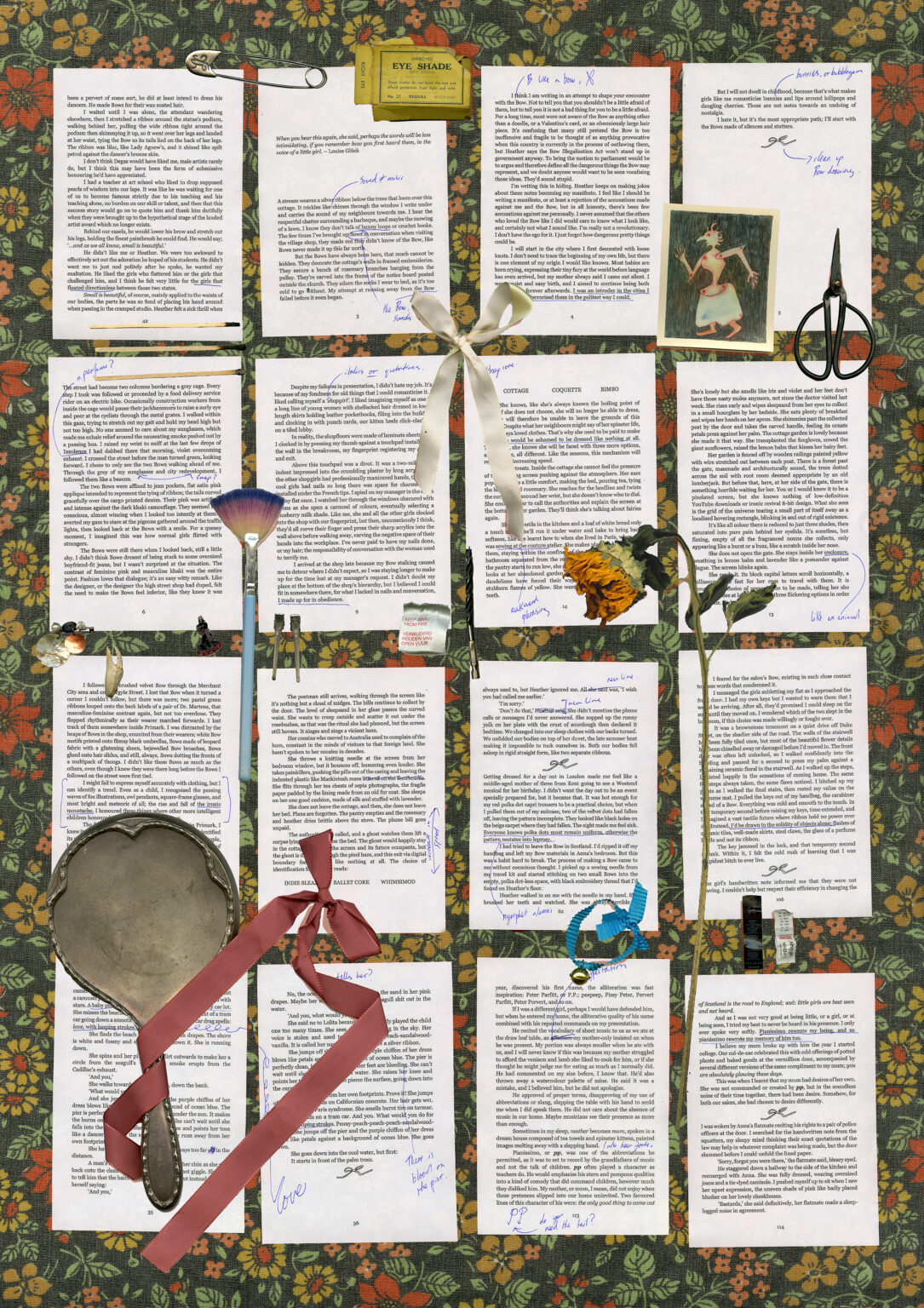

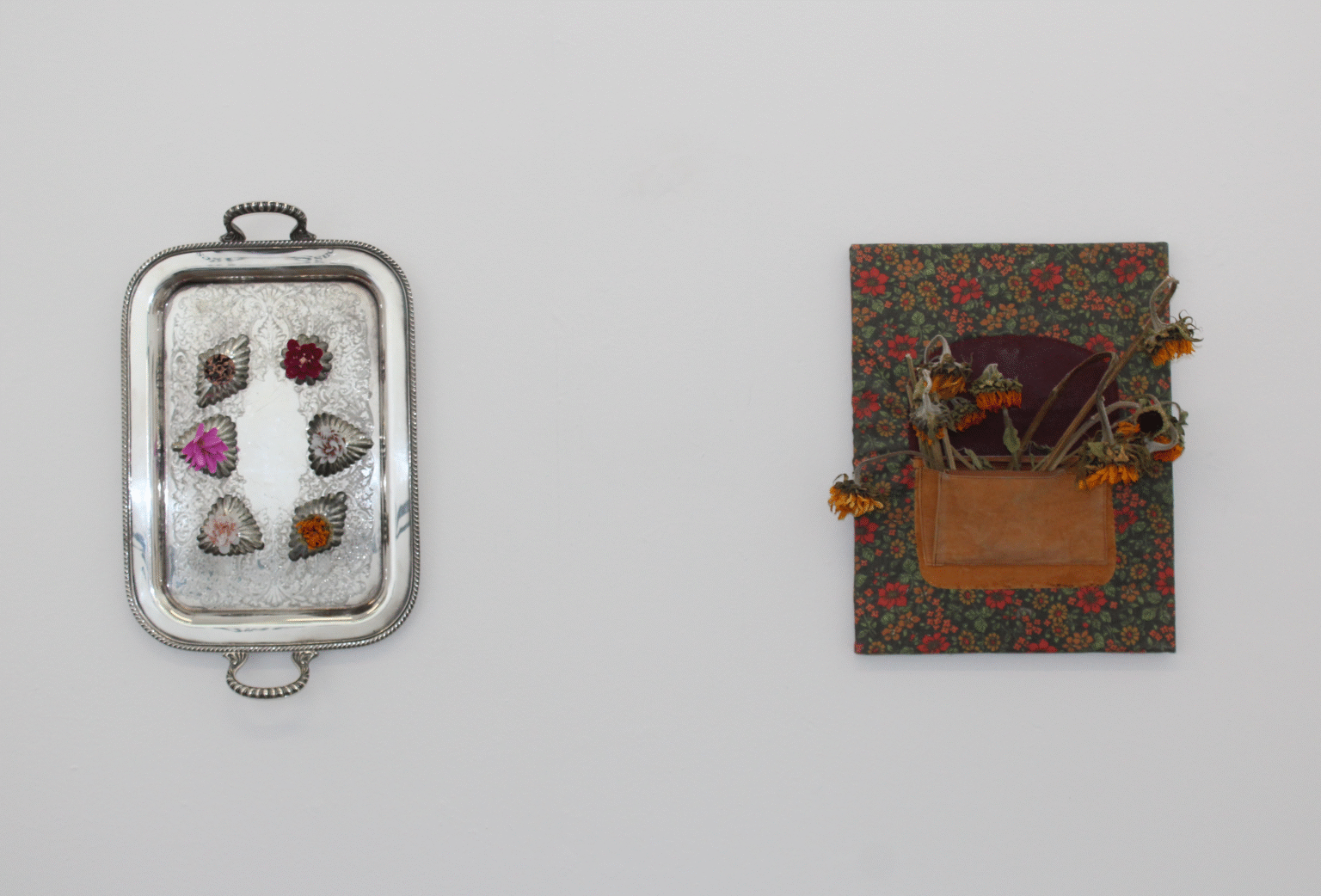

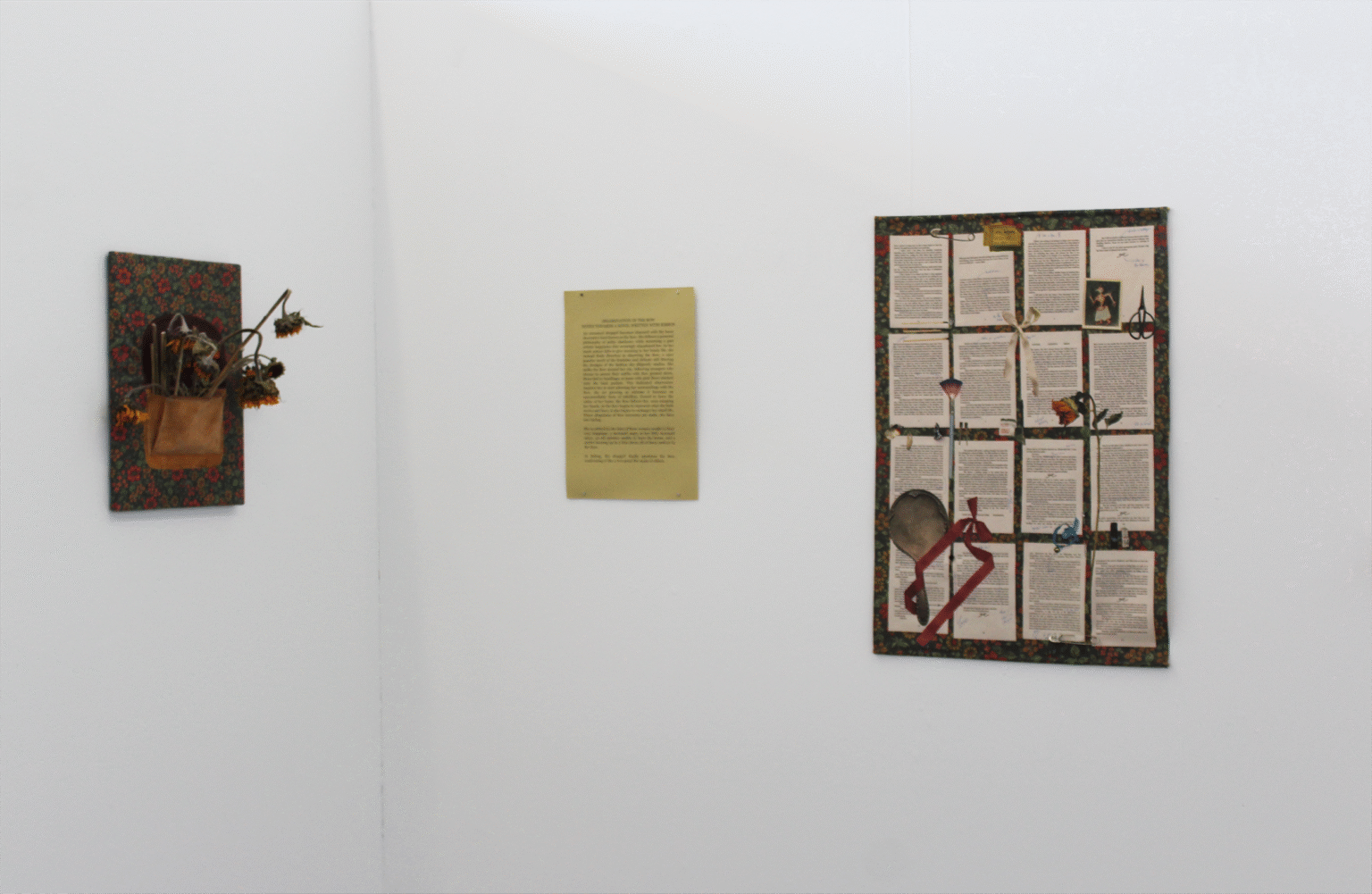

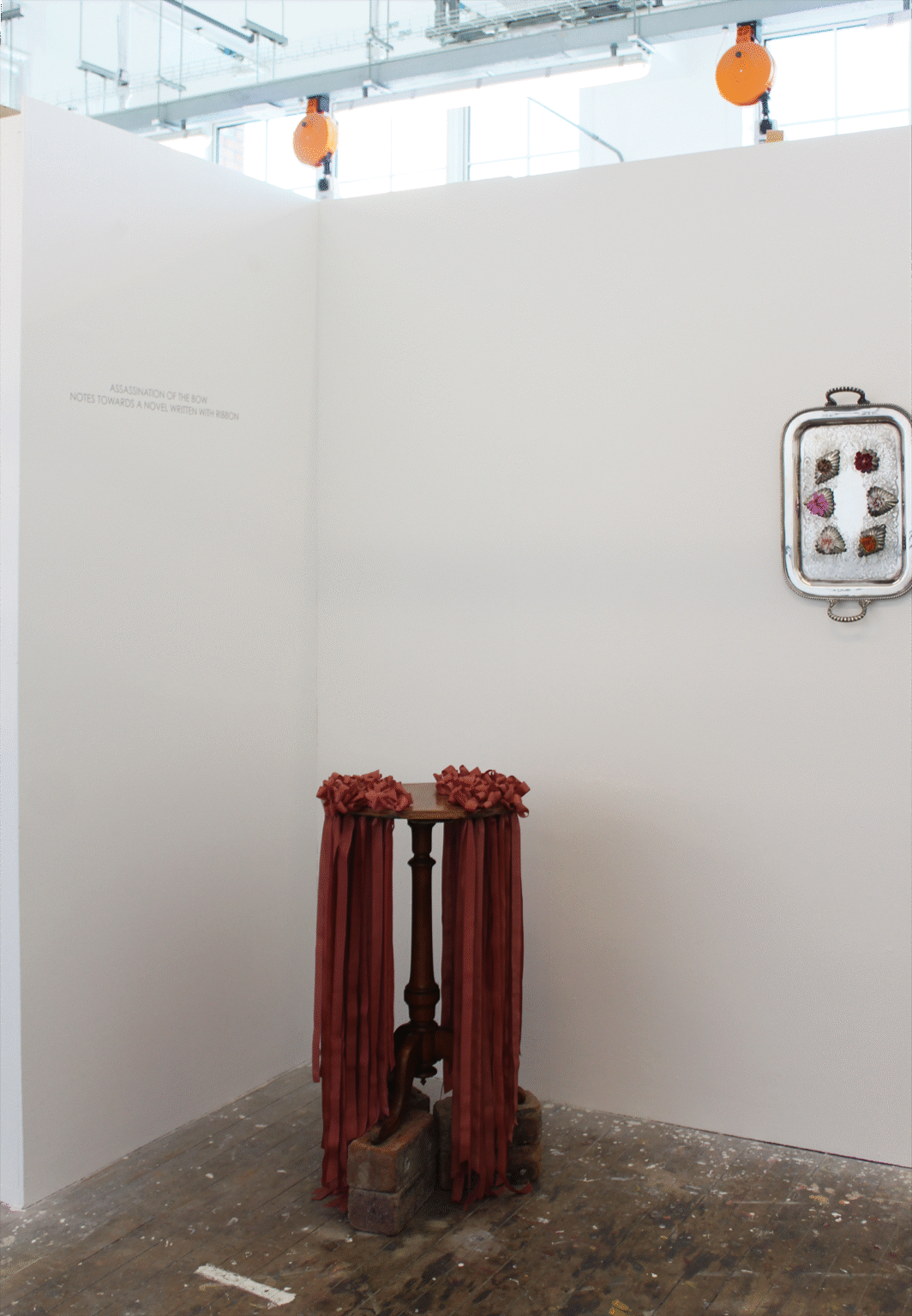

Madeleine Kaye is an artist and writer from the East Coast of Scotland. Her practice is concerned with intimacy, femininity, contradiction, and the olfactory. Assassination of the Bow: Notes Towards a Novel Written with Ribbon is a body of sculptural work made alongside a manuscript for a novel, which is a fictional narrative examining the loose decorative knot known as the bow.

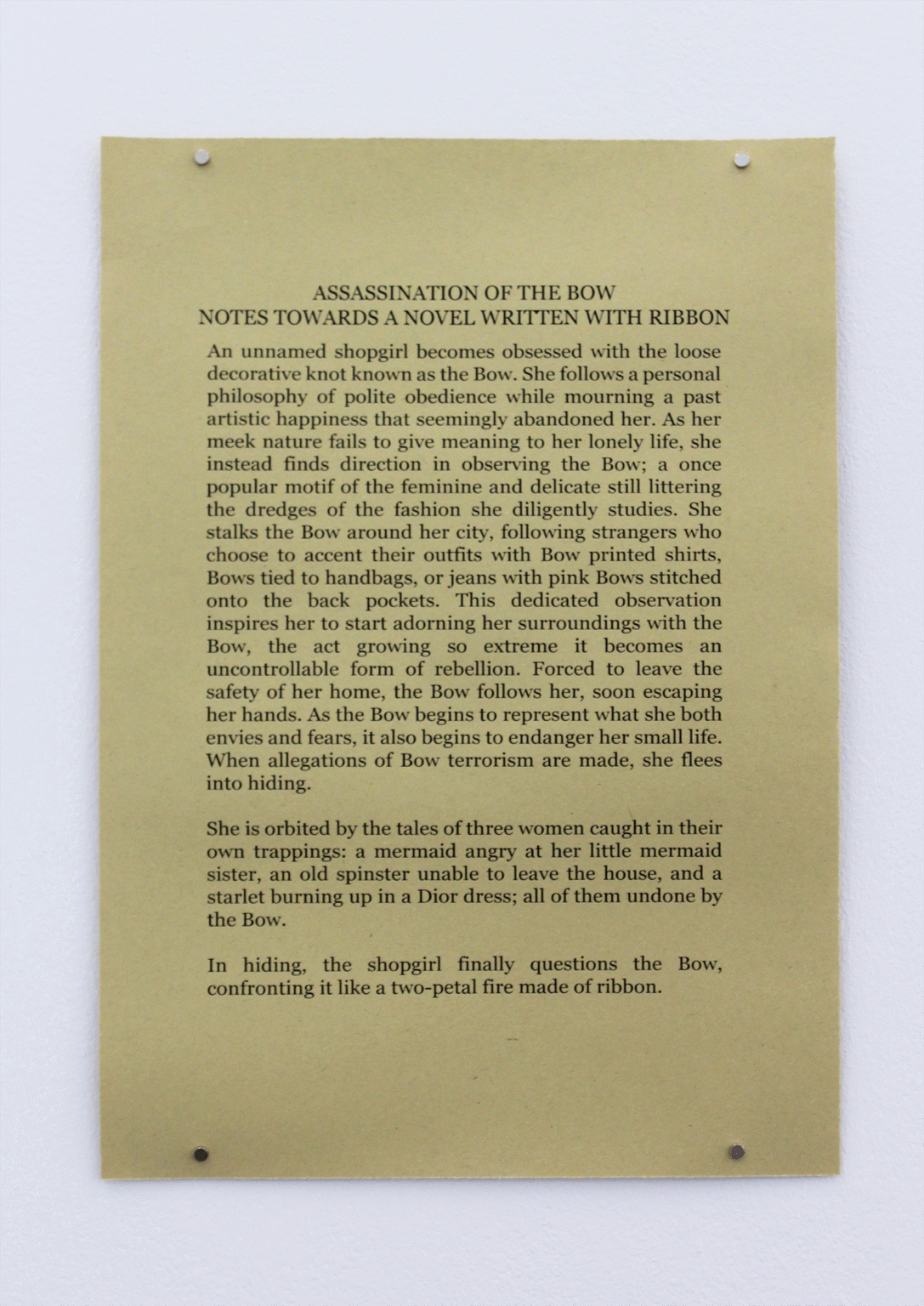

An unnamed shopgirl becomes obsessed with the loose decorative knot known as the Bow. She follows a personal philosophy of polite obedience while mourning a past artistic happiness that seemingly abandoned her. As her meek nature fails to give meaning to her lonely life, she instead finds direction in observing the Bow; a once popular motif of the feminine and delicate still littering the dredges of the fashion she diligently studies. She stalks the Bow around her city, following strangers who choose to accent their outfits with Bow printed shirts, Bows tied to handbags, or jeans with pink Bows stitched onto the back pockets. This dedicated observation inspires her to start adorning her surroundings with the Bow, the act growing so extreme it becomes an uncontrollable form of rebellion. Forced to leave the safety of her home, the Bow follows her, soon escaping her hands. As the Bow begins to represent what she both envies and fears, it also begins to endanger her small life. When allegations of Bow terrorism are made, she flees into hiding.

She is orbited by the tales of three women caught in their own trappings: a mermaid angry at her little mermaid sister, an old spinster unable to leave the house, and a starlet burning up in a Dior dress; all of them undone by the Bow.

In hiding, the shopgirl finally questions the Bow, confronting it like a two-petal fire made of ribbon.

AN UNTYING

‘Girl stuff is dangerous, let’s use it to our advantage.’ – Julia Serano, The Barrette Manifesto

I began from a point of insecurity. My sculptural practice is led by material choices that I rarely feel the need to defend, but when these materials –fake nails, broken handbags, vintage baking paraphernalia, etc.– appeared in my writing, I realised an insecurity in my ability to claim a feminine presentation. A relationship to femininity is never easy, and my practice has never simply been a critique or defence of the cosmetic ornamentation my materials may symbolise. It is the contradiction of my fondness for these things which led me to consider their radical potential.

This process coincided with a recent resurgence in the motif of the bow. Once you start looking for loose knots with two loops and two tails, they appear everywhere.

The bow as motif exists in close relation to contemporary ideas of girlhood. Personally, I can identify many aesthetic stylings connected to this popular idea of girlhood via my Instagram feed. In this space, girlhood no longer only encompasses ‘the state or time of being a girl’[1] but becomes a socially defined concept built around a set of fashionable visuals and ideas.

Two phrases of note to have emerged during this girlhood mania, are girl math, or girl dinner, both describing mundane and messy parts of a femme life. Girl math referring to the illogical mathematics used in arguing for frivolous purchases, and girl dinner referring to a series of snacks instead of a single meal. Girl math has been critiqued for its suggestion that women should not be trusted to deal with their own finances,[2] and girl dinner has been criticised for suggesting that avoiding substantial meals is a habit to be encouraged as a form of weight loss for women.[3]

It’s inevitable I’m afraid, this ‘skinny’ behaviour leads us back to fashion. Coquette, a French word meaning a playful or fickle and flirtatious woman,[4] has been used to name a style particularly proud of the bow. Coquette curiously resembles an aesthetic descendant of the imagery used in media inspired by Nabokov’s Lolita, far more than the subculture which first claimed the Lolita name.

Lolita style developed in Tokyo and is heavily inspired by Western Victorian and Romantic clothing. It favours crinolines, petticoats, and frills, often with a gothic colour scheme. The dresses tend to be knee-length, heavily layered, and rarely revealing.[5] Coquette fashion takes some inspiration from Lolita subculture, with a romantic Rococo influence superseding the Victorian. Dresses are often lighter, with shorter hemlines, and done in pastel colouring. It is also important to note, that both subcultures openly prefer pale skin, a racist intonation possibly linked to their historical inspirations; the colonial powers of Victorian Britain and Regency France.[6]

The bow’s place in fashion can also be seen in the SS2024 collections of Miu Miu, Simone Rocha, and Sandy Liang,[7] and before that, less overtly coquettish bows were seen in the SS2022 collections of Comme des Garçons, Richard Quinn, and Moschino.[8]

The bow’s association with coquette is best seen online, where coquette is often symbolised with a single emoji: the pink bow.

When comparing the bow to other motifs that have once embellished contemporary female fashion, such as bubble-gum,[9] lollipops, and the Playboy Bunny[10] (all motifs which were hugely popular during my childhood), the bow has come to symbolise a very different type of femininity. These other motifs are layered with a sexuality stemming from both overt and metaphoric ideas. There is Playboy, the men’s magazine featuring nude female models, and then the lollipop, placed between Lolita’s lips,[11] and even more lips, with bubble-gum blown seductively from them. These motifs have typical suggestions of the immature made sexual; the secretive strip tease and the body made consumable in relation to candy. I believe the bow is parallel in weight of meaning, and it is made even more powerful in its ability to contradict itself within these meanings.

The bow’s contradictory presence is that it both conforms and subverts sexual connotations. It is an opening signalling the arrival of sensuality; a string dress strap slipping from the model’s shoulder, the untying of a corset, a mouth made in any other form. The bow can also be a closed entry, a weak barrier created to defend sensuality; tied up too tight, a corset secured and unlikely to be undone. Crucially, when the bow does possess a lack of eroticism, this state appears to arise from its suggestions of a young and immature femininity; pigtails tied with ribbon, frilly dresses designed to please little girls and not men, a flower girl proud of her sash belt. Today, fashion’s mainstream use of the bow appears to purport a self-defined innocence, or even, an asexuality. But this innocence struggles to remain profound, as again, we fall back into a sexuality stained with the Lolita narrative, wherein the unassuming girl becomes a sexual object not in spite of her innocence, but due to it.

Coquette, girlhood, and the bow, can combine to create a figure which contains many of the signifiers of the white damsel archetype –sexual innocence, fragility, and an inability to deal with one’s own finances (girl math)– as identified by Ruby Hamad in White Tears/Brown Scars:

And so “white damsel” as an archetype was one of racial purity, Christian morality, sexual innocence, demureness, and financial dependence on men all rolled into one. A privilege, yes, but a perilous one, for to step off this pedestal meant to no longer be regarded as a “woman.”[12]

Girlhood today, and its bow, does not refer to an experience of childhood, but a list of burdens and desires and hierarchies. Thinking of the bow as a metaphor which so richly represents many contradictory states, has led me to developing a story wherein the narrator becomes obsessed with the bow and all it may offer her, as a young woman who is deeply insecure in her expression of femininity.

I use the term ‘femme’ alongside but not interchangeably with ‘feminine’ to situate this project in the context of queer theory which resists restrictive ideology that dictates the rules and boundaries of gender expression.[13] I am also aware of an asexual and aromantic quality to my writing, which may stem from an intention of avoiding a romantic narrative, but also allows for an exploration of the narrator’s alluring appearance to be built not in response to another.

A trans-femme writer who has written on this contradictory fondness for pretty or feminine objects, is McKenzie Wark in The Politics of Cuteness:

The pretty things emerge into the world to challenge it: to be forms without norms and not without a struggle.[14]

Here, prettiness is not an unfortunate connotation but is an essential element in the controversial potential of these objects. A prettiness, or cuteness, that is derived from femininity but not solely of femininity, can be subversive in its discomfort. It can be part of a creative process in producing the material of actualisation. I was also attracted to how Wark uses girl in resistance to infantilisation:

Cute reverses a certain feminist disdain for the girl as powerless, immature and infantilized. What if, instead, the girl was the path to evading the boredom of patriarchy?[15]

The confident use of girl in place of woman, or the femme, reminds me of Lisa Robertson’s argument towards the percussive use of the word in The Baudelaire Fractal:

If I repeat the word girl very often, it’s for those who, like me, prefer the short monosyllable, its percussive force. I wonder if in repeating I might exhaust the designation that fixed me, flood it with the lugubrious excess it named, and so convert the diminutive syllable to a terrain of the possible. Maybe this would be grace. Maybe. Would it be grace to aesthetically yield to the mystic obscenity of the word girl?[16]

Like Wark, Robertson writes towards a subversive femme that indulges in the mystic vulgarness of its existence. This is also done in The Barrette Manifesto, Julia Serano,[17] wherein the fear of being seen as feminine becomes a playful but menacing political power. The miraculous capacity of prettiness and girlhood is in its ability to both conform and subvert, much like the bow.

I wanted to portray this symbolic potential of the bow, with its weighted negative and positive meanings in Assassination of the Bow. But before it undoes my narrator, she finds meaning and direction from it. By stalking the bow as it appears to her in the city, primarily on the outfits of strangers, she is aligned with the flaneur. She gives way to urban exploration:

With Bows a bright, soaring sight across the city, spaces that I had never seen before became open to me.

…

I walked and I walked, brazen and intoxicated by my freshly decorated world.

The Baudelaire Fractal offers a view of the flaneur that allows for a femme understanding of the city, indulging in Charles Baudelaire’s, and modernity’s, love for fashion. Garments, or body adornment, map what was previously unmapped for the femme:

‘Garments can translate a city, map a previously unimagined mode of freedom or consent.’[18]

It is through the city that the bow becomes rejoiceful for the narrator again and again, even when troubled. When fashion’s resurgence of the bow takes a commercial and willingly ignorant apolitical turn, the narrator thinks of Angela Carter’s writing on 60s fashion:

In the decade of Vietnam, in the century of Hiroshima and Buchenwald, we are as perpetually aware of mortality as any generation ever was. It is small wonder that so many people are taking the dandy’s way of asking unanswerable questions. The pursuit of magnificence starts as play and ends as nihilism or metaphysics or a new examination of the nature of goals. In the pursuit of magnificence, nothing is sacred.[19]

But the bow in the city subverts this, and the narrator finds hope again, in seeing how the bow can bloom there:

My love had only manufactured its capital reemergence. I read Tweets about the Bow resurgence from my secret accounts, think pieces and style analysis, and felt smug, knowing what those journalists didn’t. The Bow was not ironic or vintage. They just became again, from me and discarded fabric. It wasn’t just the Bow as accessory. The Bow bloomed outside too, isolated from my efforts. I would see lost objects or barren lots, places I would naturally run towards, hoping to tie ribbon around the separate parts and unite them whole, only to find a Bow already in place.

Assassination of the Bow is written within the many awkward contradictions I have outlined; where the bow is both sinister and soft, kind and cruel, an opening and a closing, a political power and a willing ignorance, accepting and rejecting, a loud flirtation and a silent child. It is made towards a beauty that is untied and then tied again.

And now, I think of Shola Von Reinhold’s Lote:

But even the Greeks must at one point have realised the importance of ornament. They called the universe “kosmos”, meaning decoration, surface, ornament; something cosmetic. Like makeup. Like lipstick! Like rouge. The cosmos is fundamentally blusher. [20]

In the cosmetic beauty of the femme and feminine, things are easily wiped away or untied, but in constantly remaking and remembering, the narrator can move towards a gender expression and life that is both obliged and freed. She may enter the universe alone and also, not, but always decorated.

[1] Girlhood, Oxford English Dictionary, n.d.

[2]Alaina Demopoulos. ‘Can’t we have a funny joke?’ Why #girlmath is dividing’ (Guardian, 2023) <https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/sep/28/girl-math-tiktok-joke-women-sexism>

[3] Morgan Fargo. ‘Girl dinner is being co-opted to promote deeply unhealthy body ideals’ (Cosmopolitan, 2023) < https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/body/diet-nutrition/a44760818/girl-dinner-tiktok-trend/>

[4] Coquette, Oxford English Dictionary, n.d.

[5] Masafumi Monden. A Dream Dress for Girls: Milk, Fashion, and Shōjo Identity (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019) p.211

[6] Ian Kumamoto. ‘Gen Z has fallen in love with the coquette aesthetic’ (Time Out, 2024) <https://www.timeout.com/newyork/news/gen-z-has-fallen-in-love-with-the-coquette-aesthetic-but-its-not-all-ribbons-and-bows-020224>

[7] Tara Gonzales. ‘Bows are back in a big way’ (Harpers Bazaar, 2024) <https://www.harpersbazaar.com/uk/fashion/a46264205/bow-trend-explained/>

[8] Kristen Bateman. ‘The Rise and Fall –and Rise Again–of the Fashion Bow’ (Harpers Bazaar, 2021) <https://www.harpersbazaar.com/fashion/trends/a38390932/bows-in-fashion/

[9] Constance Grady. ‘The bubblegum misogyny of 2000s pop culture’ (Vox, 2021) <https://www.vox.com/culture/22350286/2000s-pop-culture-misogyny-britney-spears-janet-jackson-whitney-houston-monica-lewinsky>

[10] Isiah Magsino. ‘How the Playboy Brand Got a Second Chance at Life’ (Spy, 2022) <https://spy.com/articles/gear/style/playboy-apparel-2022-1202857796/>

[11] Rachel Arons. ‘Designing “Lolita”’ (The New Yorker, 2013) < https://www.newyorker.com./books/page-turner/designing-lolita>

[12] Ruby Hamad. ‘Only White Damsels Can Be in Distress’ White Tears/Brown Scars: How White Feminism Betrays Women of Colour (Trapeze, 2020) p.65

[13] Judith Butler. ‘Identity, Sex, and the Metaphysics of Substance’ Gender Trouble (Routledge, 1990)

[14] McKenzie Wark. ‘The Politics of Cuteness’ (Frieze, 2024) <https://www.frieze.com/article/mckenzie-wark-politics-cuteness-246>

[15] Wark. (2024)

[16] Lisa Robertson. The Baudelaire Fractal (Peninsula Press, 2020) p.73

[17] Julia Serano. ‘The Barrette Manifesto’ Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity (Seal Press, 2016)

[18] Robertson (2020) p. 13

[19] Angela Carter. Nothing Sacred (Virago, 1982) p.88

[20] Shola Von Reinhold. Lote (Jacaranda, 2020) p.312